By Richard Torné

OK, let’s get this over quickly. If you’re a bloke, it’s highly probable that one of your childhood dreams was to become a fireman, and if you’re a woman…do the words ‘calendar’ and ‘charity’ perhaps spring to mind?

Gender stereotyping aside, fire-fighters belong to that select group of professionals the public invariably look up to because they seem to represent the best in us – it’s a powerfully compelling image. After all, who can forget that image of exhausted fire-fighters lying on the ground like rag-dolls the morning after the Grenfell Tower blaze?

It was a poignant footnote to a terrible tragedy which pulled at the collective heart-strings of the entire nation. There was an implicit understanding that, however beaten they looked, they would have lifted themselves up, dusted themselves down and charged back into the inferno without a moment’s hesitation.

Turre’s fire-fighters may hopefully never have to confront such hellish scenes, but after guarding over the Levante area of Almería for more than 20 years, no-one doubts they would if they had to.

The station’s chief, 50-year-old Paco Flores, has been in charge from the start, although you wouldn’t think the pressure has ever got to him, judging by his jovial manner. “We had no fire trucks at the beginning. Instead, we lugged around rucksacks containing 30 litres of water with a pump,” he says with a smile.

A serious fire in Cortijo Grande more than 24 years ago led a Scottish businessman to donate the first two fire trucks (the handover ceremony was covered by UK TV at the time), and not long afterwards Flores obtained a subsidy to buy an additional two fire tenders.

They’ve never looked back since. The two original fire trucks, a lowly Bedford van and a Dodge with the steering wheel on the right, now lie quietly rusting away in a corner behind the station, while Flores gets to choose all the new equipment from a specialist mail-order catalogue.

Despite the obvious improvements, there are concerns the service is being stretched. Turre’s fire-fighters now have to shuttle to Albox to man that town’s station, all thanks to political fumbling following a fall-out over funding last year between Albox council and the provincial government, Diputación.

The station was temporarily closed before being hastily re-opened in January with a skeleton staff of about two. Put simply, while there are 12 vehicles to service the Levante there are only two in Albox to cover the entire Almanzora valley. Firemen know they would struggle to cope if two, large fires were to break out simultaneously in the Almanzora and the Levante, and although there are plans to increase the force by 26 more firemen, they’re keeping their fingers crossed that nothing major happens until then.

I follow the team on an emergency call out to a reported fire near Sorbas. Chasing the pack along the motorway’s exciting, the climax less so. Drivers on the A-7 motorway, alarmed at the sight of what appeared to be smoke billowing from below a bridge, had in fact seen nothing more than dust being kicked up from the hooves of sheep.

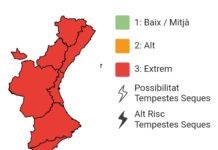

But the threat of wildfires is very real. In the first week of August alone, more than 8,000 hectares of Spanish countryside went up in smoke, according to the ministry of agriculture. And in the first six months of the year there have been double the number of fires across the country compared to 2016.

So far the Levante has been largely spared, with only two, relatively minor, bush fires in the last two months. “People are more aware now, but we’ve had five wild fires by the side of the road recently. You can sometimes see from the way it’s started that it was caused by discarded cigarette butts,” Flores reveals.

By contrast, car fires have been more common – eight since the beginning of July. Many are due to poor vehicle maintenance, but the increasing use of aluminium in car bodies is an added hazard as the alloy reacts with water and burns more fiercely, often leading to a catastrophic meltdown. Fire-fighters also have to take extra precautions with airbags, as these can accidentally deploy while trying to free a crash victim.

As in any job, there’s a routine. With firemen, it’s a daily check on equipment to ensure everything works as it should – it could make the difference between life and death. “The last thing you want is for something to fail just when you need it most,” veteran fire-fighter Felipe Gómez tells me.

Among his pet peeves are drivers who freeze and fail to get out of the way when a fire tender, sirens blaring, is dashing to an incident. “Some get nervous and simply brake. My advice is to just get out of the way.”

Carlos Artero, one of the younger firemen at the station, is reticent about discussing the more harrowing aspects of the job, but he gradually opens up. Four years ago they were called out to deal with an accident on the A-7 motorway near Sorbas, when a BMW somersaulted over the barrier and landed on its side. When they arrived, they were met with a chilling scene. “It was a family of four – father, mother and their two daughters. Two were already dead. The man’s body was lying on top of one of the girls who had survived the crash but was pinned down, and her arm was badly crushed under the car. It seemed to take forever to get the two survivors out of the wreck.

“Some people are very lucky. In one crash, the car fell on the female driver after rolling several times before coming to a rest on a ‘rambla’ (dry river bed), but she walked away without a scratch.”

Every fireman handles stress differently, but chief Flores simply shrugs when asked how he copes with emotional trauma. “There are times when it’s hard, but I feel it’s the same as being a doctor. The worst part is when you meet the relatives of the deceased at the scene of a traffic accident and you have to stop them from getting through.”

It takes three months to train a fire-fighter, but Flores stresses that the learning process continues “for the rest of your life”. I note that there aren’t any female fire-fighters in Turre. He says he would have no problem employing one – as long as they pass the tests. “There was one in Albox and there’s one now in Almería (she was recruited in January). I thought it was a very positive move.” It sounds a bit like a standard PC response. When I ask if he believes women are less physically capable than men, he dodges the question. “I don’t want a ‘wardrobe’ (a big bloke) who is psychologically weak working for me, I prefer a balance between physical and mental attributes.” Presumably that goes both ways, but he admits women have to pass slightly less stringent tests to enter the fire service. For instance, to get top marks, men are expected to do 20 repetitions on the pull-up bar; while it’s 17 for women.

But why would anyone want to become a fire-fighter, anyway? “When you know that you’ve saved a life with your work, it’s worth it. I’ve had better paid jobs before, but this is the best one I’ve ever had.” Maybe it’s not too late to get my Fireman Sam colouring book out.